As a young student of enology, Jorge Monzón traveled to Burgundy. Despite not speaking a word of French or having […]

Keep ReadingAs a young student of enology, Jorge Monzón traveled to Burgundy. Despite not speaking a word of French or having any recommendations, let alone experience, he convinced Domaine La Romanée-Conti to take him on as an intern. His eagerness and desire to learn led him to shadow maître de chai, Bernard Noblet, observing all the steps he took to create the famed wines of this historic Domaine.

Returning to Ribera del Duero and his hometown of La Aguilera, Jorge worked a couple of years at Vega Sicilia, attempting to create a white wine to rival the estate’s reds before becoming the technical director at Arzuaga-Navarro. While working for others, Jorge began purchasing old vineyards around La Aguilera – parcels in danger of being ripped up and replaced with more productive clones of Tempranillo as well as “fashionable” Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Petit Verdot, and Malbec. These undesirable vineyards were ancient, unproductive massale selections of Tempranillo mixed with a diverse range of other varieties, including a high proportion of white grapes – all “useless” in a region that prized extraction, production, and the everything new and shiny.

Jorge’s years at DRC only focused his vision and conviction that terruño and tradition matter. His vineyards, some planted before phylloxera, or right after it struck, were planted exactly as they had been for centuries – predominantly Tempranillo with a wide genetic diversity alongside Albillo, Tempranillo Gris, Cariñena, Garnacha, Bobal, Bruñal and others so obscure that they haven’t been identified yet. Ranging in age from 60-150+ years old, it is surprising that these vines survived at all considering the recent trends in Ribera del Duero.

With his wife, Isabel Rodero, Jorge founded Dominio del Águila in 2010, and they have expanded their vineyards to 66 hectares. Farming is certified organic and Isabel, an architect, supervised the renovation of three ancient cellars dating to the 15th century dug deep into the bedrock under the village. Natural yeast, whole cluster co-fermentations are the first step in the process with pigeage done by foot. After primary fermentation, the wines are placed in oak barrels for malo and aging. Their cold, subterranean cellars ensure that their wines’ evolution proceeds slowly, allowing for the development of greater complexity and nuance.

Dominio del Águila’s vineyards are all located around the village of La Aguilera – so in that sense, they are all village wines. They sell much of their fruit selecting the best for their wines. Pícaro Clarete & Tinto are field blends, selected from parcels chosen for their quality and response to vintage conditions.

The Reserva comes from vines planted before 1930, on sandy clay-limestone soils, and utilizing all the varieties present in the vineyard to add complexity to the Tempranillo. Pena Aladas is a zone within the village of La Aguilera. The soils are thin, sandy clay over hard limestone bedrock. The structure of the fruit grown in Pena Aladas requires a long period in oak to soften, evolve, and open up. The goal is not to make a Gran Reserva because it was expected, but because the terroir demanded it. Canta la Perdiz is a single vineyard wine made from vines between 100 and 150 years, with many ungrafted vines. The soils here are shallow, gravelly clay over a friable and horizontally fractured limestone. With a softer structure than Pena Aladas, it requires less time in barrel and shows a wildly aromatic and floral aspect that sets it apart from the other sites that Jorge and Isabel farm.

Various versions of Albillo are planted in the vineyards of Dominio del Águila including two rare, small parcels that are planted entirely with Albillo. Although the D.O. didn’t recognize white wines until 2019, Jorge felt that his best vines of Albillo – small clusters of deeply golden berries – demanded to be segregated and made into a tiny production white wine first commercially produced in 2010. It is a D.O.-defining wine and one unlikely to be emulated.

CloseIsabel and Jorge survey their tiny kingdom of vines

A classic view of Ribera del Duero - fertile soils planted with grains, poor soils with vines.

Isabel and Jorge in Las Matillas

Sprawling old vines in Las Matillas

Conejos Vineyard

Layered vine (ungrafted) in La Encerrada - the connection between the the two vines was never cut in this instance

Old vine in El Picón del Melo

Old vine in El Fuentarron

El Fuentarron vineyard

The scattered plots in Peña Aladas

Canta la Perdiz

Canta la Perdiz

The village of La Aguilera

The village of La Aguilera

The village of La Aguilera

The village of La Aguilera

Stairway to heaven?

Three 15th-16th century cellars have been renovated and linked under the guidance of architect Isabel Rodero

Each barrel is transported painstakingly down into the subterranean cellar

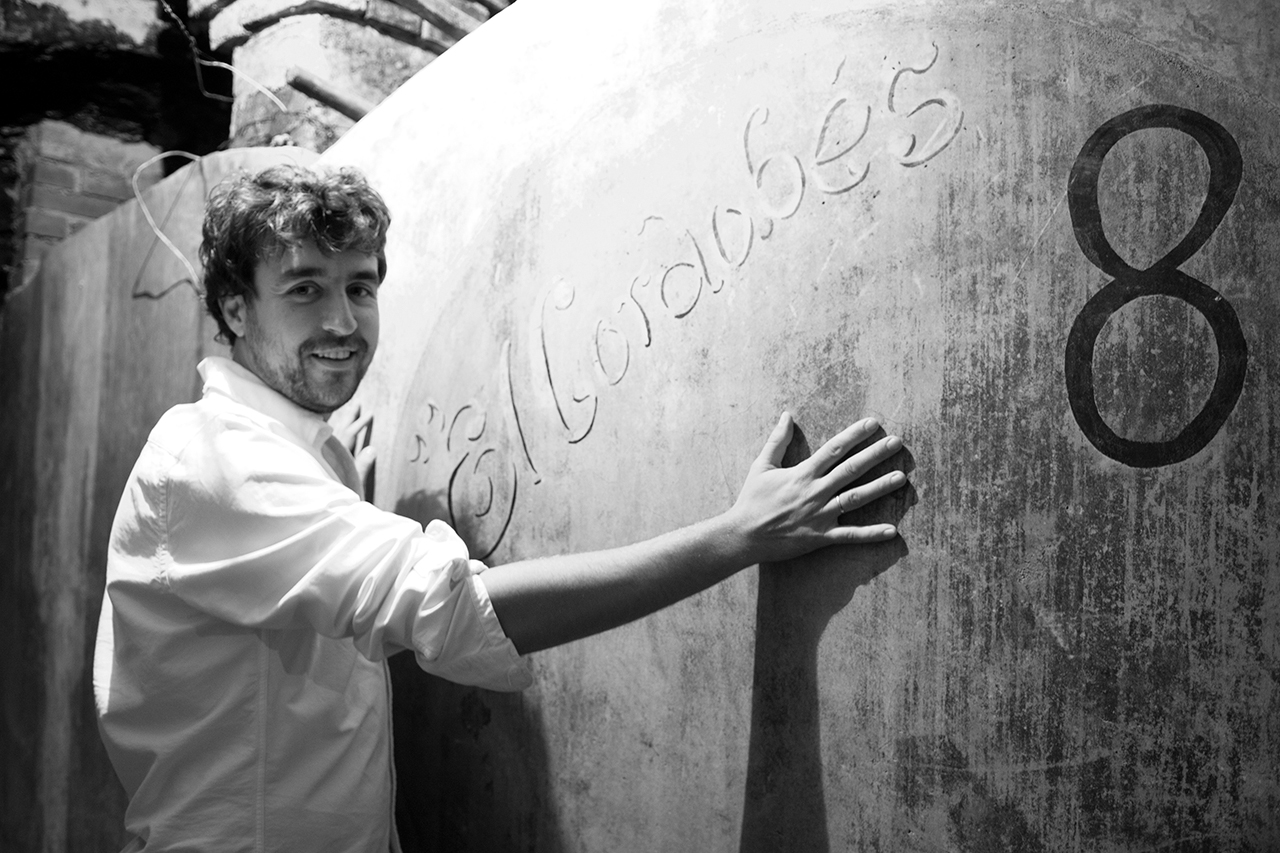

Jorge Monzón and Isabel Rodero in Consejo